|

|

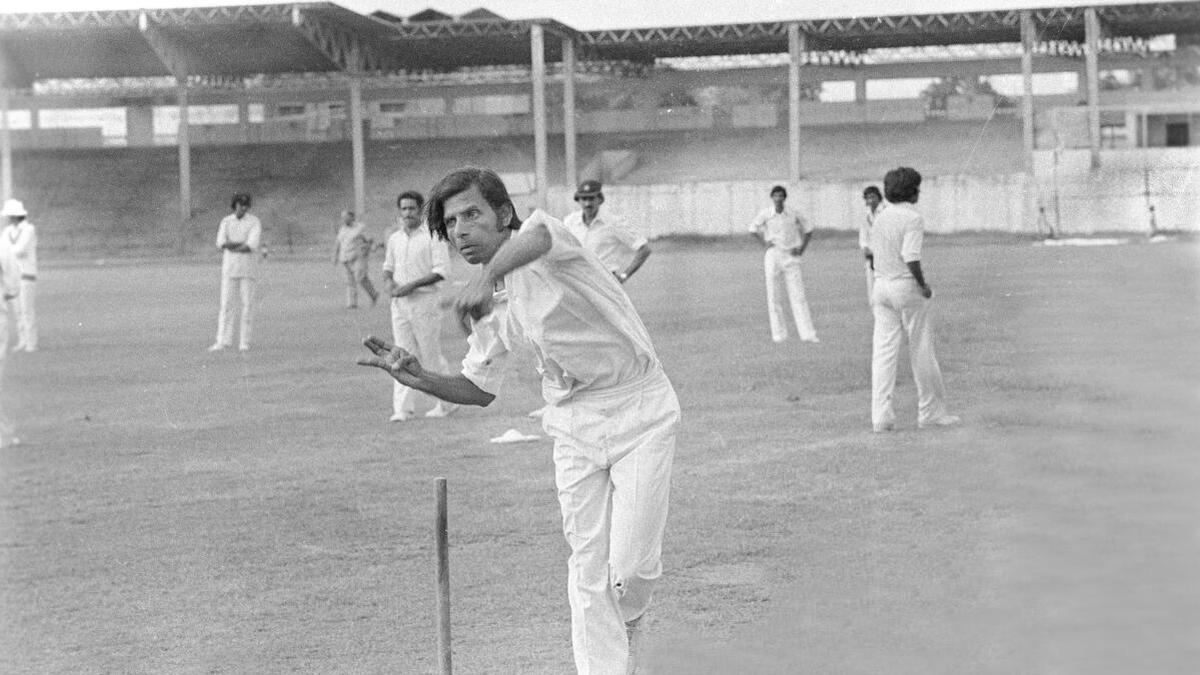

Padmakar “Paddy” Shivalkar’s story is a captivating tale of serendipity, exceptional talent, and unfulfilled potential within the realm of Indian cricket. This left-arm orthodox spinner, who tragically never donned the Indian national colours, etched his name in domestic cricket folklore with his mesmerizing spells and unparalleled skill. Shivalkar, in his own words, was a cricketer “by accident.” His entry into the sport wasn't driven by childhood dreams or years of rigorous training; rather, it was a practical solution to securing employment. In a time when office cricket teams offered jobs to talented players, the young Shivalkar, struggling to find work after three years of fruitless searching, saw an opportunity. He accompanied a friend to the nets, despite having minimal experience with a cricket ball, his prior experience limited to tennis ball cricket. His first attempts with the hard ball were inauspicious, sending the first two deliveries into the net on either side of the wicket. However, guided by his friend’s advice to aim for the middle stump, his very next ball crashed into the sticks, revealing a natural talent for left-arm orthodox spin. This single delivery changed the course of Shivalkar's life. Observing from the sidelines was none other than Vinoo Mankad, a legend in Indian cricket, renowned as one of the country’s greatest left-arm spinners and all-rounders. Mankad offered Shivalkar a job on the spot, recognizing the raw potential he possessed. More importantly, Mankad imparted a crucial piece of advice that shaped Shivalkar's career: “Don’t copy me. Find your own style. If you copy me, you will be finished.” Shivalkar took these words to heart, developing a unique style that would make him a force to be reckoned with in domestic cricket for the next two decades. The shadow of Vinoo Mankad's guidance was instrumental in Paddy’s evolution. Instead of attempting to replicate Mankad's already established style, Shivalkar nurtured his distinct approach, focusing on flight, guile, and subtle variations in spin. This willingness to forge his own path was key to his extraordinary success in the years that followed. While Mankad gave Shivalkar his initial opportunity, the onus was always on the young bowler to transform potential into performance, a challenge Paddy met with unwavering dedication and a deep love for the game. Shivalkar’s career wasn't without its disappointments. Despite his exceptional performances, he was consistently overlooked for a place in the Indian national team. However, this did not diminish his passion for cricket or his commitment to his craft. He remained a devoted student of the game, always seeking to improve and pass on his knowledge to younger players. His philosophical outlook allowed him to accept his fate with grace and focus on what he could control, his performance on the field and his contribution to the sport. Shivalkar's story serves as a reminder that success in cricket, or in any field, is not solely determined by talent or opportunity. It requires dedication, perseverance, and the ability to learn and adapt. His unyielding commitment to mastering the art of spin bowling and his philosophical approach to the game made him a role model for aspiring cricketers, even if he never achieved the international recognition he deserved.

Shivalkar’s talent was quickly recognized. In March 1962, at the age of twenty-two, he was drafted into the CCI President’s XI to play against an International XI led by Richie Benaud at the Brabourne Stadium. Bowling alongside Baloo Gupte, the younger brother of leg-spinner Subhash Gupte, Shivalkar made an immediate impact. He took five wickets in the first innings, including the prized scalps of Everton Weekes, Raman Subba Row, and Benaud himself. In the second innings, he dismissed Weekes again and added Tom Graveney to his list of victims. These performances showcased his immense potential and raised hopes for a future in the Indian team. However, these dreams were never realized. He spent years waiting for his opportunity to replace Bapu Nadkarni in the Bombay team. Once he finally got his chance, his genius was unleashed. He single-handedly bowled Bombay to victory on countless occasions, but it was the final of the Ranji Trophy in Chennai in 1973 that truly cemented his reputation as a bowling maestro. Bombay’s batting lineup in 1973 was a who’s who of Indian Test cricket, featuring legends like Sunil Gavaskar, Ajit Wadekar, Ashok Mankad (Vinoo Mankad’s son), Dilip Sardesai, Sudhir Nayak, and Eknath Solkar. They faced a formidable Tamil Nadu spin attack led by V.V. Kumar and Srinivas Venkataraghavan on a Chepauk pitch designed to favor spin. Winning the toss and batting first, Bombay's vaunted batting lineup could only manage a modest 151, with Kumar and Venkat each taking five wickets. Tamil Nadu, in response, started poorly, losing two wickets with their score at 6. However, Michael Dalvi and Abdul Jabbar steadied the ship, taking the score to 62 for 2 by the end of the first day’s play. The next day was a rest day, and Shivalkar recounted a conversation he had with his roommate Solkar that evening. He had noticed Venkat bowling with more flight than usual, making it difficult for the Bombay batsmen to play him. He told Solkar that he was going to take a chance and do the same the next day, despite it being Venkat’s home pitch. This conversation illustrates Shivalkar's keen observation skills and his willingness to adapt to the conditions. Despite being an experienced bowler, he wasn't afraid to try something new and challenging, even on a turning track that favored the home team’s spinners. This adaptability and strategic thinking were key to his success in the Ranji Trophy final and throughout his career. The ability to read the pitch, understand the opponent's strengths and weaknesses, and adjust his bowling accordingly were hallmarks of Shivalkar's genius. His meticulous attention to detail and his willingness to experiment set him apart from other spinners of his time. His decision to mimic Venkat's flight, despite it being a risky strategy, demonstrates his confidence in his ability to execute his plans under pressure. The conversation also reveals his close relationship with Solkar, who served as a confidant and sounding board. This camaraderie and mutual support were essential to the team’s success.

On the second day of the match, Shivalkar's first ball turned and bounced sharply. Leg spinner V.V. Kumar, who was sitting in the pavilion and slated to bat at No. 11, turned to Kalayanasundaram, the No. 10, and said, “Change into whites. Both of us will be batting within an hour.” Kumar’s prediction proved accurate. Shivalkar proceeded to dismantle the Tamil Nadu batting lineup, reducing them to a mere 80 all out. His figures were an astounding 8 for 16. Only the overnight batsmen reached double figures. The 71-run lead that Shivalkar gave Bombay proved to be crucial as its batsmen failed again on a pitch that had become even more difficult. They were bundled out for 113 in their second innings, leaving Tamil Nadu to score 185 to win. However, by preparing a surface to help their spinners, the hosts had inadvertently played into Shivalkar’s hands. This time, Shivalkar and Solkar were the wreckers-in-chief, picking up 5 wickets each, as Tamil Nadu collapsed to 61 all out. Shivalkar's match figures were an incredible 13 wickets for 34 runs. His magnificent spin bowling had almost single-handedly brought home the Ranji Trophy. This performance was a testament to Shivalkar's skill, his mental fortitude, and his ability to perform under pressure. He rose to the occasion when his team needed him most, delivering a match-winning performance that will be remembered for years to come. The hosts' underprepared pitch plan had spectacularly backfired, highlighting the dangers of over-preparing a surface to suit one's own bowlers. Shivalkar's performance demonstrated that a true spinner can thrive on any surface, as long as they have the skill and guile to exploit the conditions. This was not the only time that opponents underestimated Shivalkar’s impact. In the previous Ranji season, he had run through Mysore’s famed batting lineup, which included Gundappa Vishwanath and Brijesh Patel, in the semi-finals, returning figures of 8 for 19 and 5 for 31. Tamil Nadu should have known better. These consistent performances against top-quality batsmen demonstrated Shivalkar's ability to perform at the highest level. He was not a one-match wonder; he was a consistent performer who could be relied upon to deliver when it mattered most. This consistency is what made him such a valuable asset to the Bombay team and why he was so highly regarded by his peers. His ability to bowl long spells, maintain accuracy, and deceive batsmen with his variations made him a nightmare for opposition captains.

In a first-class career spanning twenty-six years, from 1961-62 to 1987-88, Shivalkar took 589 wickets at an incredible average of 19.69 and an economy rate a shade above 2. These statistics speak volumes about his talent and his dedication to the game. He was a prolific wicket-taker who consistently troubled batsmen with his spin. The fact that he maintained such a low average and economy rate over such a long period is a testament to his skill and consistency. Despite his domestic success, Shivalkar was always philosophical about his inability to make it into the Indian side. He continued to be passionate about the game well into his 80s. He was rarely to be found in anything other than in whites during the day, passing on his wisdom to younger players. He believed in giving back to the sport and helping the next generation of cricketers. This selflessness and dedication to the game are what made him such a beloved figure in Indian cricket. The author recalls an incident where Shivalkar called him on the morning of the launch of his book Spell-binding Spells in 2017 and hesitantly asked if it was okay to come in his whites since he would not have time to go home and change. The author was stunned by Shivalkar's humility. This anecdote highlights Shivalkar's down-to-earth nature and his unwavering commitment to cricket. Despite his accomplishments, he remained a humble and approachable figure, always willing to share his knowledge and experience with others. It has often been pointed out that Shivalkar lost out on a Test place to Bishan Singh Bedi, who took 1,560 first-class wickets. However, the author argues that this is not a particularly convincing argument. Ajit Wadekar once said, “Had I been the chairman of selectors, on most occasions I would have convinced the captain to play both in the team depending on the nature of the pitch. If (Erapalli) Prasanna and Venkat could be in the team, why not Bedi and Paddy?’ Wadekar's statement highlights the fact that there was no real reason why Shivalkar and Bedi could not have played together in the Indian team. They were both exceptional spinners who could have complemented each other well. The fact that they were not given the opportunity to do so is a matter of regret for many cricket fans. The author points out that after the quartet of spinners retired, Doshi and Maninder played together, as did Doshi and Shastri, and two off-spinners have operated in tandem on many occasions. He also notes that as recently as last week, three left-arm spinners played in an ODI as part of an Indian quartet. This demonstrates that there is nothing inherently wrong with playing two or more spinners in the same team. It all comes down to the captain's strategy and the nature of the pitch.

The author notes that when Wadekar was captain of India in the early 1970s, he himself did not play Shivalkar in the team alongside Bedi. He instead played Venkat. Gavaskar had the chance to pick Shivalkar early in his captaincy career but was unable to convince the selectors to do so. Be that as it may, the author concludes that it is indeed India’s loss that Shivalkar’s talent would never be on display at the highest level of the sport. This is a sentiment shared by many cricket fans who believe that Shivalkar was unfairly denied the opportunity to represent his country. When the author once asked Shivalkar if he resented the fact that he was never given a chance to play for India while lesser spinners got into the team, Shivalkar’s response was typically philosophical: ‘I was not destined to bowl for India. I have no regrets really. I played cricket and that is what matters.’ Shivalkar's philosophical outlook allowed him to accept his fate with grace and focus on what he could control, his performance on the field and his contribution to the sport. The author feels fortunate to have known Shivalkar, a man he had long admired, even if it was for the last decade of his life. Over the past few years, they spent hours talking about the game and the art of spin. At the launch of the author's book Wizards a few months before Covid, Shivalkar, in the company of Dilip Doshi and Dilip Vengsarkar, regaled the audience with stories and insights. The management of Title Waves at Bandra had to ask them to wrap up the evening as it was well after closing hours. It was Shivalkar, along with Chandra, who called multiple times during the pandemic to ask how the family and the author were coping and just to spend an hour talking about cricket and life in general. The author concludes that in addition to being a genius at his craft, Shivalkar was truly a good man. He may have left us mortals in awe of his immortal genius, but the author believes that an even better second innings is about to commence. He imagines Shivalkar and Bedi, operating from two ends of the Elysian pitch, getting ready to spin a web around Bradman’s Immortal Invincibles World XI. This is a fitting tribute to two of the greatest spinners in Indian cricket history. It is a reminder that even though Shivalkar never had the opportunity to play for India, his talent and his contribution to the game will never be forgotten.

Source: Paddy Shivalkar: Indian spin’s eternal handmaiden, a cricketer by accident