|

|

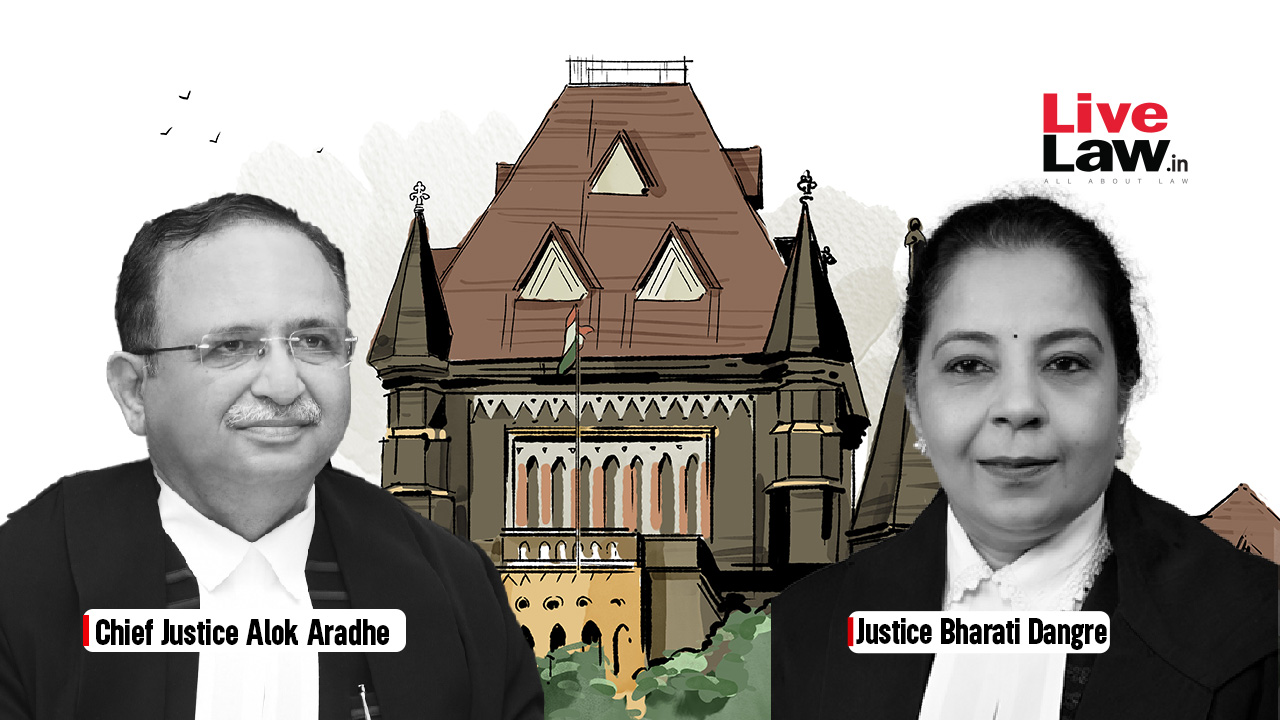

The Bombay High Court's recent judgment clarifying that resignation constitutes retirement under the High Court Judges (Salaries and Conditions of Services) Act, 1954, marks a significant interpretation of the legal framework governing the financial entitlements of High Court judges. This ruling, delivered by a division bench comprising Chief Justice Alok Aradhe and Justice Bharati Dangre, directly addresses the ambiguity surrounding the term 'retirement' as it applies to judges who choose to resign from their positions rather than retire through superannuation. The case, brought forward by Pushpa Ganediwala, a former Additional Judge of the High Court, challenged an order that denied her pension benefits based on the interpretation that resignation did not equate to retirement under the Act. This detailed essay will delve into the intricacies of the case, analyze the court's reasoning, and explore the broader implications of this judgment for the judiciary and the legal understanding of retirement and resignation in the context of public service. Ganediwala's contention centered on the argument that the term 'retirement' should not be narrowly construed to exclusively mean retirement by superannuation. She posited that the expression, within the context of Sections 14 and 15 of the High Court Judges (Salaries and Conditions of Services) Act, 1954, encompasses resignation as a valid mode of concluding one's service. This interpretation was met with resistance from the respondent authorities, who argued that resignation implies an unwillingness to continue employment and should therefore not be equated with retirement, which they viewed as a distinct and separate event primarily associated with reaching the age of superannuation. The authorities further contended that allowing pension benefits to judges who resign would be inconsistent with the spirit and intent of the Act, potentially opening the door to strategic resignations designed to secure pension benefits without fulfilling the complete tenure expected of a judge. The High Court, however, sided with Ganediwala, offering a comprehensive and nuanced interpretation of the Act. The court's reasoning hinged on the understanding that the word 'retirement' possesses a broad and inclusive meaning, signifying the conclusion of a career, regardless of the specific manner in which that conclusion is reached. The judges emphasized that one of the accepted meanings of the word 'retire' is, in fact, 'to resign.' This semantic analysis formed a crucial part of the court's rationale, highlighting the interchangeable nature of the terms in certain contexts. Furthermore, the court underscored the absence of specific language in the Act that explicitly restricts the definition of retirement to superannuation alone. If the legislature had intended to limit pension benefits solely to judges who retired upon reaching the age of superannuation, the court argued, it would have expressly included such a provision in the Act. The absence of such a restrictive clause strongly suggested that the legislature intended for the term 'retirement' to be interpreted more broadly, encompassing various modes of concluding judicial service, including resignation. The court also drew attention to the involuntary nature of retirement due to ill-health, as contemplated by clause 14(c) of the 1956 Act, further reinforcing the argument that retirement is not solely predicated on voluntary acts like superannuation. Both resignation and retirement, the court reasoned, effectively bring an end to the service career, and the mode of departure should not be the determining factor in assessing eligibility for pension benefits. Resignation, in this view, is simply one of the recognized methods of retiring from service, albeit a voluntary one. This analysis directly countered the respondent authorities' argument that resignation signifies an unwillingness to continue employment, thereby disqualifying the judge from receiving pension benefits. In support of its interpretation, the court pointed to the existing practice of granting pension benefits to five former judges of the same court who had previously resigned from their positions. The fact that these judges were receiving pensions without any apparent legal impediment undermined the authorities' argument that resignation automatically forfeits the right to pension benefits. The court questioned the lack of a consistent rationale for denying Ganediwala the same benefits that had been granted to her predecessors. The judgment underscores the importance of interpreting statutes in a manner that reflects their underlying purpose and avoids creating arbitrary distinctions that could lead to unjust outcomes. The High Court's decision to quash the impugned order and grant Ganediwala her pension benefits with effect from February 14, 2022, demonstrates a commitment to fairness and equity within the legal system. This case has far-reaching implications for the interpretation of similar provisions in other statutes and regulations governing the retirement benefits of public servants. It reinforces the principle that the substance of an action should prevail over its form, and that the term 'retirement' should be understood in its broadest sense, encompassing all legitimate means of concluding a career in public service. The decision also highlights the importance of consistency in the application of legal principles and the need for authorities to provide clear and justifiable reasons for any departures from established practices. The Bombay High Court's ruling in the Pushpa Ganediwala case serves as a significant precedent for future cases involving the interpretation of retirement benefits and the rights of public servants who choose to resign from their positions. It clarifies the legal landscape and ensures that judges who resign are not unfairly penalized by being denied the pension benefits to which they are rightfully entitled. The long-term effects of this decision are expected to resonate throughout the Indian judicial system and beyond, shaping the understanding of retirement and resignation in the context of public service for years to come. The meticulous examination of the relevant statutes and the careful consideration of the arguments presented by both sides demonstrate the High Court's commitment to upholding the principles of justice and fairness. This case stands as a testament to the importance of judicial review in safeguarding the rights of individuals and ensuring that the law is applied in a just and equitable manner.

The judgment in Pushpa W/O Virendra Ganediwala vs. High Court Of Judicature Of Bombay Through Registrar General (WP/15018/2023) delves deeper than merely resolving a pension dispute; it touches upon the essence of judicial service and the state's responsibility towards its officers. The detailed reasoning presented by the division bench provides a compelling argument against restrictive interpretations of statutes, advocating for a more holistic and contextual understanding of terms like 'retirement.' By explicitly stating that 'retirement' under Sections 14 and 15(1) of the High Court Judges (Salaries and Conditions of Services) Act, 1954, includes 'resignation,' the court dismantles a potentially discriminatory practice. This decision reinforces the idea that a judge's service, regardless of its conclusion method, should be acknowledged and compensated fairly, especially considering the sacrifices and dedication required in such a role. The argument presented by the respondent authorities, focusing on the 'unwillingness to continue in employment' implied by resignation, seems to overlook the multifaceted reasons behind a judge's decision to resign. Personal circumstances, health concerns, alternative career opportunities, or even disagreement with certain policies could all contribute to such a decision. Equating resignation with a simple lack of commitment undermines the complex realities of judicial life. The court's emphasis on the word 'retirement' as a term of 'wide import' is crucial. By acknowledging its broad meaning, the court allows for a more equitable application of pension benefits. If the legislature intended a narrower definition, restricting it to superannuation, it would have explicitly stated so. The absence of such explicit limitation suggests a deliberate choice to encompass various forms of departure from service. The comparison with 'involuntary act' of retirement due to ill-health further strengthens the argument. If involuntary retirement qualifies for pension, it becomes illogical to deny the same benefits to someone voluntarily resigning, especially when both actions result in the conclusion of their service. The court's observation about five former judges receiving pensions after resignation is perhaps the most damning evidence against the respondent authorities' argument. This precedent demonstrates a clear inconsistency in application, raising questions about the fairness and justification behind denying Ganediwala the same benefits. The lack of explanation from the authorities further exacerbates the issue, implying a potentially arbitrary and discriminatory practice. The judgment's emphasis on the mode of retirement being irrelevant for pension eligibility is a cornerstone of its reasoning. By focusing on the fundamental criterion of 'retirement' itself, the court prevents the creation of artificial distinctions based on the specific circumstances of departure. This ensures a more uniform and equitable application of the law. The decision ultimately underscores the importance of judicial independence and security. Ensuring fair compensation and pension benefits for judges, regardless of their retirement method, contributes to their financial security and independence. This, in turn, strengthens the integrity of the judiciary and its ability to function without undue influence. The Ganediwala case serves as a reminder that legal interpretations should be guided by principles of fairness, equity, and consistency. Restrictive readings of statutes, especially when they impact the rights and benefits of public servants, should be approached with caution. The Bombay High Court's judgment is a significant step towards ensuring a more just and equitable legal framework for the judiciary and potentially other branches of the public service. The clarity and persuasiveness of the court's reasoning make it a valuable precedent for future cases involving similar issues, promoting consistency and fairness in the application of retirement benefits.

Beyond the immediate implications for Pushpa Ganediwala and other similarly situated judges, the Bombay High Court's ruling invites broader reflection on the evolving nature of work and retirement in contemporary society. Traditionally, retirement was often viewed as a monolithic event, typically occurring upon reaching a specific age and signaling the end of one's professional life. However, increasingly, individuals are choosing to retire at different ages, pursuing phased retirement, or engaging in encore careers after leaving their primary employment. The Ganediwala case highlights the need for legal frameworks to adapt to these changing realities and to recognize the diverse ways in which individuals conclude their professional careers. The court's emphasis on the 'conclusion of a career' as the defining characteristic of retirement aligns with this more flexible and nuanced understanding. It acknowledges that retirement is not simply a matter of age or tenure but rather a broader process of transitioning out of the workforce. This perspective is particularly relevant in the context of the judiciary, where judges often bring extensive experience and expertise to their roles. The decision to resign may be driven by a variety of factors, including personal circumstances, health considerations, or a desire to pursue other opportunities. Denying pension benefits based solely on the mode of departure could discourage talented individuals from serving on the bench or create unnecessary financial hardship for those who choose to resign for legitimate reasons. The court's emphasis on fairness and equity in the application of pension benefits is also consistent with broader societal trends towards greater social justice and equality. Pension systems are designed to provide financial security in retirement and to recognize the contributions that individuals have made to society throughout their working lives. Arbitrarily denying these benefits based on technicalities or narrow interpretations of the law undermines the fundamental purpose of these systems. The Ganediwala case underscores the importance of ensuring that pension systems are administered in a fair and transparent manner and that all eligible individuals receive the benefits to which they are entitled. The ruling also serves as a reminder of the crucial role that the judiciary plays in safeguarding the rights of individuals and ensuring that the law is applied in a just and equitable manner. By carefully scrutinizing the relevant statutes and considering the arguments presented by both sides, the Bombay High Court demonstrated its commitment to upholding the principles of justice and fairness. This case stands as a testament to the importance of judicial independence and the need for courts to be able to exercise their authority without undue influence. In conclusion, the Bombay High Court's decision in the Ganediwala case has significant implications for the interpretation of retirement benefits and the rights of public servants. It also invites broader reflection on the evolving nature of work and retirement in contemporary society and the need for legal frameworks to adapt to these changing realities. The court's emphasis on fairness, equity, and consistency in the application of pension benefits is consistent with broader societal trends towards greater social justice and equality. This case serves as a reminder of the crucial role that the judiciary plays in safeguarding the rights of individuals and ensuring that the law is applied in a just and equitable manner. The long-term impact of this ruling is likely to be felt throughout the Indian legal system and beyond, shaping the understanding of retirement and resignation in the context of public service for years to come.

Source: Judge Who Resigned Also Entitled To Pension Benefits As Judge Who Retired : Bombay High Court