|

|

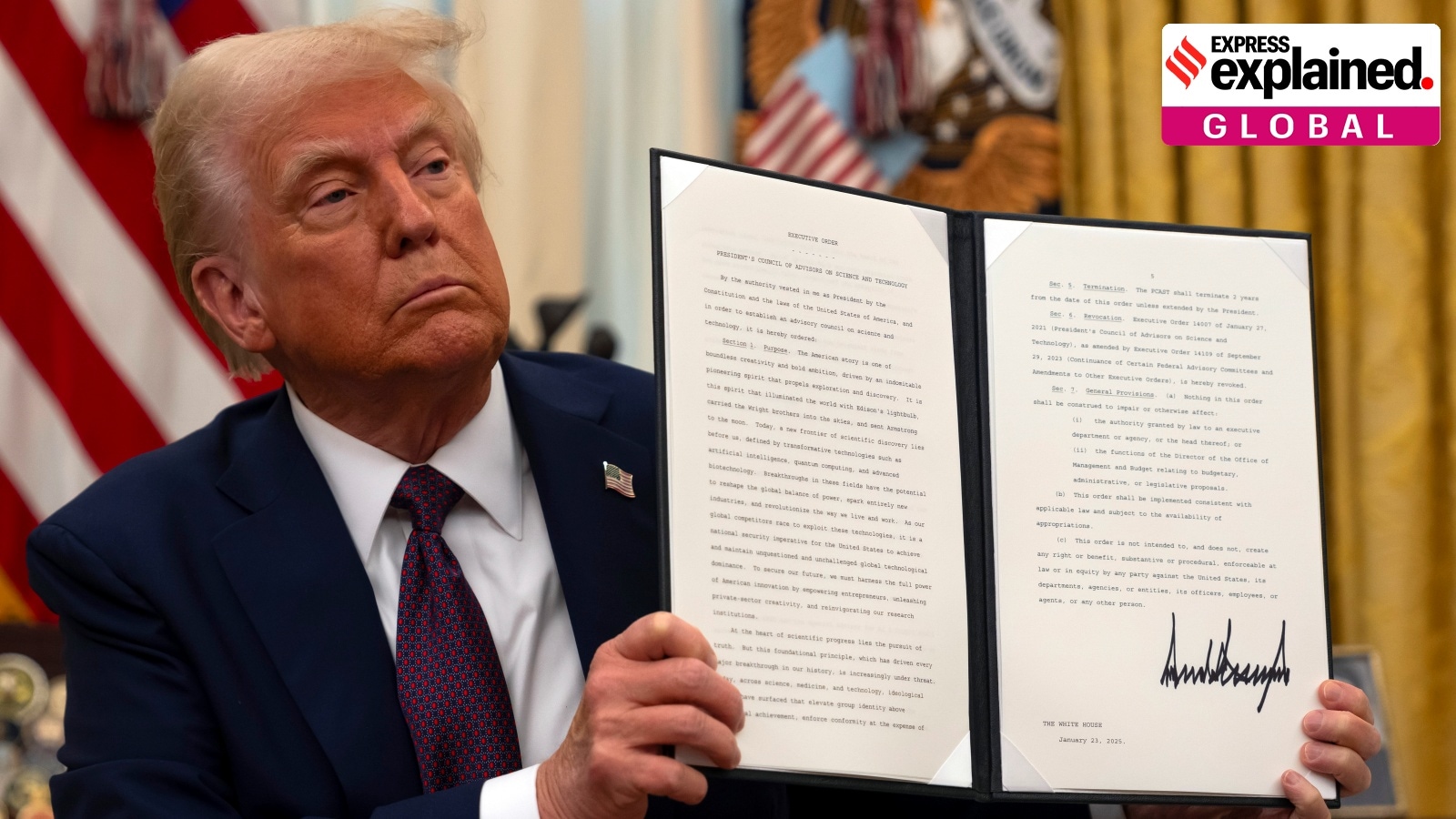

The ongoing debate surrounding birthright citizenship in the United States has recently intensified with President Donald Trump's executive order aiming to curtail this right. This action has been met with immediate legal challenges, highlighting the complex history and legal interpretations surrounding the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution. The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” While seemingly straightforward, the phrase “subject to its jurisdiction” has been the source of considerable legal interpretation and debate throughout history. This ambiguity allows for challenges to birthright citizenship, arguing that it does not apply to children born to undocumented immigrants or those born to foreign diplomats. The recent legal challenge demonstrates the ongoing struggle to define the precise scope of this constitutional guarantee. The legal battle is not simply a recent phenomenon; its roots lie deep within the historical context of the nation’s development and its evolving understanding of citizenship and belonging.

The origins of birthright citizenship in the US are multifaceted, reflecting the nation's own complex journey. Before the ratification of the Constitution in 1788, citizenship was largely determined at the state level, with varying interpretations and practices. While the concept of “natural born citizens” was mentioned in Article II of the original Constitution, it lacked a clear definition. This ambiguity fueled debate over the meaning of citizenship, specifically the difference between jus soli (right of soil) and jus sanguinis (right of blood). Leading legal scholars such as Thomas H. Lee have argued that the framers likely intended for the concept to encompass both principles. This historical understanding provides a crucial backdrop to the modern legal challenges. The Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court decision of 1857 starkly demonstrated the inequalities inherent in the early interpretation of citizenship, denying citizenship to enslaved people and their descendants. This landmark case, later overturned by the 14th Amendment, showcases the discriminatory practices that preceded the establishment of birthright citizenship as a more broadly applied principle. The 14th Amendment itself, while aiming to rectify historical injustices, did not fully resolve the ambiguities surrounding birthright citizenship, giving rise to ongoing legal scrutiny.

The Supreme Court's ruling in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) is considered a pivotal moment in clarifying birthright citizenship. The case involved Wong Kim Ark, a child born in the US to Chinese parents, who was denied re-entry to the US after a trip to China. The Court ruled in favor of Wong Kim Ark, stating that regardless of his parents' citizenship status, his birth in the US granted him citizenship. The Court emphasized that laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act could not override the clear language of the Constitution regarding birthright citizenship. This decision solidified the principle of jus soli, establishing a precedent that has shaped legal interpretations for over a century. However, the debate did not end there. The Plyler v. Doe (1982) case further addressed the rights of children of undocumented immigrants, affirming their right to education under the 14th Amendment. This ruling underscored the idea that even children of undocumented immigrants, being subject to US laws and residing within US territory, are entitled to the protections afforded by the Constitution. This ruling further highlights the ongoing tension between the constitutional guarantee of birthright citizenship and practical considerations regarding immigration and national identity.

In contrast to the ongoing US debate, India's journey with birthright citizenship demonstrates a different trajectory. While the framers of the Indian Constitution initially debated the merits of birthright citizenship versus citizenship based on descent, the concept was ultimately enshrined in the Constitution. Article 5 of the Indian Constitution granted citizenship to all those born in Indian territory before its commencement. The Citizenship Act of 1955 further codified this principle, although with some exceptions for children born to foreign diplomats or enemy aliens. However, subsequent amendments to the Act in 1986 and 2003 significantly altered the scope of birthright citizenship in India. The 1986 amendments, responding to concerns regarding migration from neighboring countries, restricted birthright citizenship to children of Indian citizens. The 2003 amendments further tightened the criteria, excluding children born to illegal immigrants. These amendments showcase how even nations that initially embrace birthright citizenship can modify its application based on changing socio-political realities. Comparing the Indian experience with the US situation illuminates the diverse ways in which nations grapple with the definition and application of birthright citizenship.

The continuing legal and political battles surrounding birthright citizenship in the US reflect deeply held beliefs about national identity, immigration, and the interpretation of constitutional guarantees. The historical precedents, from the Dred Scott decision to the Wong Kim Ark ruling, provide a framework for understanding the complexities of this issue. The legal challenges to recent executive orders aiming to restrict birthright citizenship are likely to continue, shaping the future of this fundamental right in the United States. Examining the experiences of other nations, like India, further emphasizes the dynamic and evolving nature of birthright citizenship policies across the globe. The debate is far from settled, and its outcome will have profound implications for the legal and social fabric of the United States.

Source: Explained: The birthright citizenship debate in the US